Oral white lesions, including leukoplakias, are commonly encountered in daily practice by oral health care providers, especially oral and maxillofacial surgeons. They are often investigated by biopsy examination to rule out the presence of dysplastic changes or cancer. Most white lesions are benign frictional keratoses or keratoses from inflammatory conditions (eg, lichen planus) and the diagnosis is usually evident from the histopathology. Leukoplakia is the term used for a white lesion that is precancerous and is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘‘a white plaque of questionable risk having excluded (other) known diseases or disorders that carry no increased risk for cancer.’’3 It is one of several potentially malignant oral lesions, including erythroplakia and submucous fibrosis. As such, it is essential that it be recognized because of its premalignant potential and managed accordingly and differently from other white lesions. There continues to be confusion on the use of the term leukoplakia, especially on how to manage leukoplakia in a patient whose diagnosis shows ‘‘hyperkeratosis with no evidence of dysplasia.’’ There also is no consensus on management or ‘‘best practice’’ guidelines for the management and treatment of dysplastic lesions, much less leukoplakias without dysplasia.

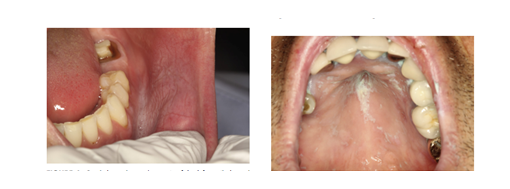

Clinically, leukoplakias are divided into homogenous and nonhomogeneous lesions. The homogeneous type is usually a thin, flat, and uniform white plaque with at least 1 area that is well demarcated with or without fissuring . Nonhomogeneous leukoplakia is characterized by the presence of speckled or erythroplakic and nodular or verrucous areas.Erythroleukoplakia can be misdiagnosed as OLP because of its white and red components. However, other clinical signs can guide the clinician to the correct diagnosis: erythroleukoplakia does not possess the typical white reticular changes and it is usually unilateral with associated welldemarcated white plaques.

Medical treatments with b-carotene, bleomycin, vitamin A, tea, and ketorolac have had no effect on malignant transformation rates, and there are no randomized control trials using surgery as the main modality of treatment to assess this outcome.102 Older frail patients could be placed on long-term follow-up, whereas it might be more appropriate to remove lesions in younger patients.

The diagnosis of true leukoplakia is based on a combination of the patient history, clinical considerations, and histopathology and is typically a diagnosis of exclusion.Leukoplakia usually has, at least in part, sharply demarcated margins, often with fissuring, and it is generally distinguishable from reactive keratoses, which are usually poorly demarcated lesions. Erythroleukoplakia tends to be less well-demarcated. Biopsy and histopathologic examinations remain the gold standard for diagnosis and are important in helping to exclude other keratotic lesions, as discussed earlier.48 Management depends on the histopathologic diagnosis and clinical presentation.

In general, the risk factors for developing oral leukoplakia are similar to those reported for oral cancer and include tobacco smoking (especially for localized leukoplakias), heavy alcohol consumption, areca nut use, ultraviolet light exposure for lip lesions, and old age. However, other factors, such as prolonged immunosuppression, a history of cancer, and a family history of cancer, are just as important but less well recognized.

Medical treatments with b-carotene, bleomycin, vitamin A, tea, and ketorolac have had no effect on malignant transformation rates, and there are no randomized control trials using surgery as the main modality of treatment to assess this outcome.Older frail patients could be placed on long-term follow-up, whereas it might be more appropriate to remove lesions in younger patients.

For More Info, Visit: https://www.santosh.ac.in/